INTRODUCTION

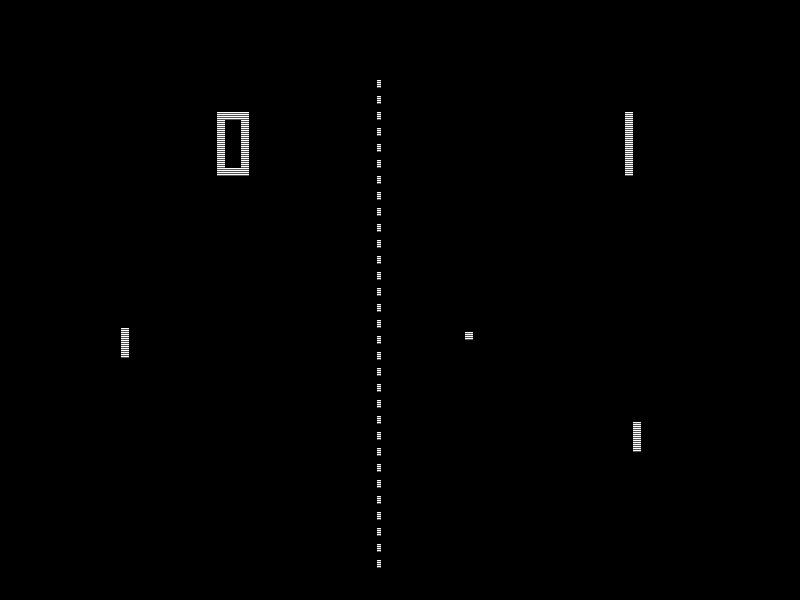

Since the first iteration of the Magnavox Odyssey hit the consumer market in 1972, players became active agents in manipulating digital worlds. Although almost unfathomably simple relative to the technical milestones that modern video gamers are accustomed to, players of the "paddle-based" Pong experienced an unfolding narrative in many of the sames ways modern gamers are currently experiencing when safeguarding the character of Clementine from zombies (The Walking Dead), rescuing Elizabeth from a life of imprisonment (Bioshock Infinite), or escorting Ellie across the United States to possibly save the world from a fungal-based outbreak turned apocalypse.

Since the first iteration of the Magnavox Odyssey hit the consumer market in 1972, players became active agents in manipulating digital worlds. Although almost unfathomably simple relative to the technical milestones that modern video gamers are accustomed to, players of the "paddle-based" Pong experienced an unfolding narrative in many of the sames ways modern gamers are currently experiencing when safeguarding the character of Clementine from zombies (The Walking Dead), rescuing Elizabeth from a life of imprisonment (Bioshock Infinite), or escorting Ellie across the United States to possibly save the world from a fungal-based outbreak turned apocalypse.

The narratives created by players playing Pong may be labeled as simple relative to the three contemporary video game narratives as described above, yet they are narratives non-the-less. As these players from the 1970s unboxed their first Odyssey consoles, connected the hardware, and sunk hours of their lives into marveling at their own capacity to control the "ball" and volley it back and forth, back and forth, and back and forth across the screen with their friends, stories were created. Stories about how the competition and rivalry between player/paddle A and player/paddle B deepened throughout their experience with the game. Stories about how player/paddle A's "ball" just snuck past player/paddle paddle. Stories about how a group of engrossed Pong players "trained" to achieve the "highest score" and gain bragging rights over the budding community of competitive players.

The narratives created by players playing Pong may be labeled as simple relative to the three contemporary video game narratives as described above, yet they are narratives non-the-less. As these players from the 1970s unboxed their first Odyssey consoles, connected the hardware, and sunk hours of their lives into marveling at their own capacity to control the "ball" and volley it back and forth, back and forth, and back and forth across the screen with their friends, stories were created. Stories about how the competition and rivalry between player/paddle A and player/paddle B deepened throughout their experience with the game. Stories about how player/paddle A's "ball" just snuck past player/paddle paddle. Stories about how a group of engrossed Pong players "trained" to achieve the "highest score" and gain bragging rights over the budding community of competitive players.

As player bases boomed and the mainstream, consumer market demonstrated to the world that there truly was an interest in video games/gaming, budding hardware and software manufacturers began to work toward capitalizing on and creating experiences that utilized the individual audience member's own agency to create a variety of narratives. Nintendo's first consumer console, the Nintendo Entertainment System, released in 1983, pushed the medium's capacity for storytelling as the hardware's relative computational capability afforded software developers the ability to develop more complex expressions of otherwise traditional literary storytelling techniques in digital form (e.g., setting, atmosphere, characters, conflict, plot arc, etc.). In contrast to the extremely minimalist expression of Pong Nintendo's Super Mario Bros. establishes a clearly identifiable/relatable setting, protagonist, and antagonist. Although equally minimalistic relative to today's technological capabilities, the digital expression of traditional literary techniques allowed player agents of Super Mario Bros. to not simply watch Mario fight foes to rescue the Princess, but to literally become Mario and battle the antagonists themselves to create their very own narratives of what it was like to rescue the Princess. In this form of early digital story telling, the narrative ended the same for all player agents, yet the "journey" to the resolution became a relatively unique experience across different player agents.

No comments:

Post a Comment